Inside Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh’s Marriage, a Roller Coaster Fueled By Passion and Jealousy

Inside Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh’s Marriage, a Roller Coaster Fueled By Passion and Jealousy

They were the original Brad and Angelina.

BY MARIA CARTER AUG 31, 2017

n her personal planner, Vivien Leigh documented the demise of her first marriage with five simple words. The 1937 artifact, soon to be auctioned by Sotheby’s, contains two telling scribbles from the Gone with the Wind icon: “Told Leigh” (June 10) and “Left with Larry” (June 16).

Thus began one of the highest profile relationships Hollywood has ever seen, a marriage that would span two decades before finally crumbling under the weight of extramarital affairs and mental illness.

Olivier took notice of Leigh around the same time the rest of England did, during her run in the play The Mask of Virtue. Before that, the 23-year-old was primarily a mother (to 5-year-old Suzanne) and wife to an older husband, barrister Herbert Leigh Holman, who humored what he hoped was merely a fleeting interest in acting for Leigh. With her newfound fame, Leigh began frequenting the Grill Room at Westminster’s swanky Savoy Hotel. That’s where she ran into Olivier, 29, and his wife, Jill Esmond.

Olivier had married Esmond, the daughter of two well-known British actors, because, he believed at the time, he “wasn’t likely to do any better at my age and with my undistinguished track-record,” her wrote in his 1982 autobiography Confessions of an Actor. The marriage had very little physical intimacy, however, because Esmond preferred women, according the 1992 biography Laurence Olivier. That didn’t stop the couple from conceiving a child: Esmond learned she was expecting their firstborn around the same time Olivier’s affair with Leigh began in early 1936. Their son, Tarquin, arrived in August.

“I couldn’t help myself with Vivien. No man could,” Olivier said. “I hated myself for cheating on Jill, but then I had cheated before, but this was something different. This wasn’t just out of lust. This was love that I really didn’t ask for but was drawn into.” (Olivier biographers Terry Coleman and Michael Munn allege Olivier cheated with others during his affair with Leigh.)

London’s Old Vic theatre cast Olivier as the lead in Hamlet in 1937, and Leigh’s calendar shows she went to see the play on numerous occasions. The lovers starred opposite each other in Fire Over England shortly after, and traveled to Denmark to perform Hamlet together (Leigh played the part of Ophelia).

On their return to England, they informed their respective spouses that the marriages were over, and promptly moved in together in Iver, Buckinghamshire. The couple spent a month apart when Olivier moved to Hollywood to film Wuthering Heights in 1938. “I woke up absolutely raging with desire for you my love…Oh dear God how I did want you,” Olivier wrote to Leigh in an undated letter experts believe was penned in 1938 or 1939. “I love you with, oh everything somehow, with a special kind of soul,” he continued.

Leigh joined him in California a month later, she said, “partially because Larry’s there and partially because I intend to get the part of Scarlett O’Hara,” according to 2003’s Vivien Leigh: A Biography.

Seemingly unable to get enough of each other, the pair looked for ways to be together professionally, too. Both were disappointed when Gone with the Wind producer David O. Selznick chose Olivier, but not Leigh, for his next project, Hitchcock’s Rebecca. He placed Joan Fontaine as the female lead instead, arguing it was best for Olivier and Leigh to keep their romance off-screen until their divorces were finalized.

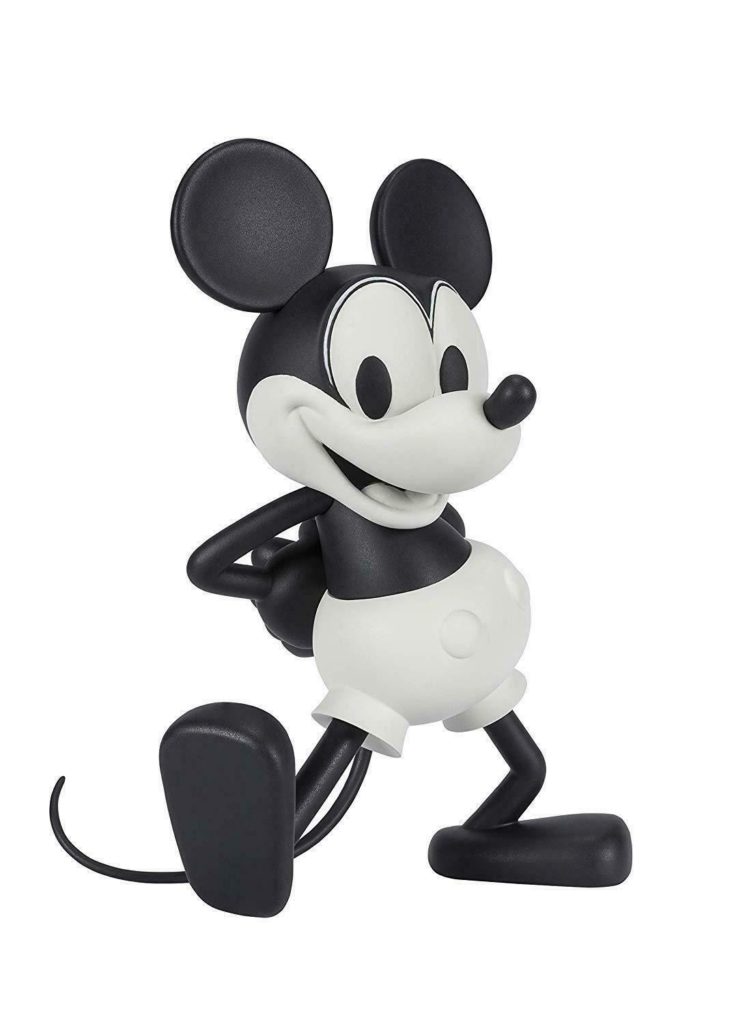

Mickey Mouse Plane Crazy Mickey 1920s Figuarts ZERO Statue

- Highly detailed 5-inch Mickey Mouse statue.

- Celebrate the 90th anniversary of the hugely popular character with Tamashii Nations figuarts zero line!

- Design based on Mickey Mouse seen in the classic movie, “plane crazy”…

GETTY IMAGES

That wish was granted in early 1940, when both of their first marriages were terminated by February. They tied the knot at San Ysidro Ranch in Santa Barbara on August 31 that year. Olivier, who wanted to help Britain’s efforts in World War II, made several propaganda films during the time and began flight training, racking up nearly 250 hours of flight time in the U.S. The couple moved back to their home country shortly after, where Olivier was stationed with the Royal Air Force at a training squadron. Sources who were close to the couple at the time saw the marriage already coming apart at the seams: Leigh had developed a drinking problem and Olivier seemed bored of her smothering affections. English playwright Noël Coward remarked that Olivier “looked unhappy” after visiting the couple at RAF Worthy Down.

However, the marriage’s true downfall began several years later, in 1948, when the couple completed a six-month theatre tour of Australia. It was during this time, Olivier later remarked, that he “lost Vivien.” They met Australian actor Peter Finch, with whom Leigh would have a years-long affair with, during the trip. Unknowingly adding fuel to the fire, Olivier auditioned Finch and placed him under contract with his production company, giving Finch a reason to move to London.

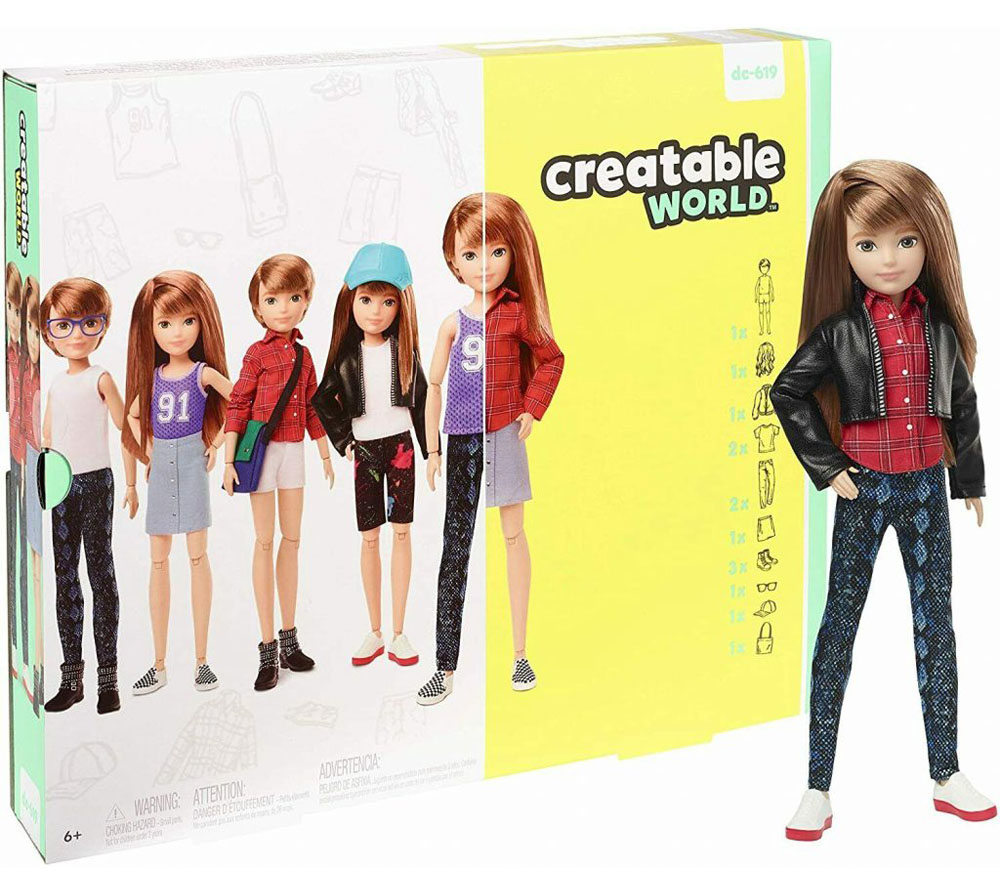

CREATABLE WORLD GGG53 Deluxe Character Kit Copper Straight Hair

- Inspire all kids 6 years and older with a Creatable World Deluxe Character Kit and let them play freely so kids can be kids and toys can be toys!

- Deluxe Character Kit DC-619 includes a doll, a wig, clothing and accessories that can be mixed and matched to create …

Leigh’s mental health began to decline in the early 1950s, and Olivier would often find her “inconsolable…sitting on the corner of the bed, wringing her hands and sobbing, in a state of grave distress,” he wrote in his autobiography. Leigh’s manic depression, as her condition was later diagnosed, proved an ” uncannily evil monster.”

Even after Leigh admitted to cheating with Finch, in 1953, the Oliviers didn’t give up on their marriage. Leigh learned she was pregnant in 1956, and resigned from the play she was in as a result. Tragically, she miscarried the day after her last performance. The incident triggered a deep depression that lasted for months. Not long after, Olivier began an affair with actress Joan Plowright, a married woman 22 years his junior.

Olivier and Leigh in 1957WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Leigh’s emotional instability worsened, and by 1960, she was threatening suicide. “Vivien is several thousand miles away, trembling on the edge of a cliff, even when she’s sitting quietly in her own drawing room,” Olivier reportedly said of his wife’s mental state, according to Lord Larry.

Their divorce proceedings began in May 1960; Leigh was quick to play the victim, telling reporters of Olivier’s relationship with Plowright. With the divorce final that December, Olivier, then 53, married Plowright, 31, and the couple welcomed a son a year later, and two daughters in the following five years.

Though never again romantically linked, Olivier and Leigh kept in touch until her death from tuberculosis in 1967. Olivier wrote to Leigh shortly after their divorce, wishing her happiness. “I want to say thank you for understanding it all for my sake,” his letter reads. “You did nobly and bravely and beautifully and I am very oh so sorry, very sorry, that it must have been much hell for you.” In his final letter just five weeks before her death, Olivier signed off with, “Sincerest love darling, your Larry.”